China’s modern art scene is a remarkably complex development that only began after the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, yet has since exploded into a broad and multifaceted movement that has garnered critical acclaim and the attention of international art collectors.

Stars Art Group

The Stars Art Group is widely considered as having laid the foundation for contemporary Chinese avant-garde art. Initiated by Huang Rui and cofounded by Ma Desheng, this small yet rebellious group of avant-garde artists rose to prominence when they staged an unsanctioned exhibition of over 100 artworks from 23 artists, set up on the fence and surrounding trees outside the National Art Museum of China in September 1979. After being forcibly removed, the group retaliated by organising a landmark protest march in Beijing on October 1, on the 30th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. They were allowed to reopen, ultimately garnering an attendance rate of almost 80,000 people. The group remained active between 1979 and 1983, staging various exhibitions, demonstrations and public readings. Notable artists include Wang Keping, Ai Wei Wei, Ah Cheng and Li Shuang.

These young artists were focused on championing freedom of expression in a cultural landscape where individuality was being increasingly restricted, and often derided the state-sanctioned Social Realism style in favour of a more experimental, avant-garde approach. While still being supportive of Chinese socialism, these young artists hoped that China would aspire toward a more open and free socialist nation, a hope that would soon be dashed in the Tiananmen Massacre in 1989. Unfortunately, the group dissolved in 1983 due to political pressure and official criticism, with many significant members choosing to immigrate out of China.

‘85 Avant-Garde Movement

Spurred by the government’s renewed receptivity toward the West, Chinese artists began to look toward Western cultures and ideas as a new source of inspiration. Written works from Europe and America were translated and disseminated among the arts community, and numerous scholarly conferences were held both locally and abroad. From this fresh intellectual environment, a new artistic movement emerged, one driven by spiritual liberation and new modes of thinking. Between 1985 and 1986, more than 2,250 young artists organised themselves into 79 groups, holding an astonishing 149 exhibitions across China. Their work was supported enthusiastically by critics, writers and editors, many of whom were young artists directly involved in the movement themselves. Among these artists were Wang Guangyi, Zhang Peili, Geng Jiayi, Huang Yongping, Gu Wenda and Wu Shanzhuan, all alumni of the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Art.

Though influenced by Western theories such as Primitivism and Conceptualism, these young Chinese artists were also interested in tackling issues close to home: freedom of expression, religious traditions, contemporary art, and minority culture, among others. Most rebelled against the strictly Realist styles that were taught in art academies, taking it upon themselves to adopt a deeper, more authentic voice while incorporating mediums such as graphic design, sculpture, readymades, and performance.

The ’85 Avant-Garde movement culminated in the momentous 1989 “China/Avant-Garde” exhibition, which was held in the National Art Museum of China in Beijing. Curated by Gao Minglu, the exhibition included 297 works in various mediums, including paintings, sculpture, photography, video, performance and installation, and brought together experimental artists from across China. Initially, the exhibition struggled to obtain approval from the authorities due to its often explicit and controversial works, such as Wang Guangyi’s Mao Zedong No. 1, which depicted the iconic Chinese leader behind a sombre black and white grid. Even after it was finally approved, the exhibition was closed twice during its run: the first closure occurred only three hours after the exhibition’s opening, when artist Xiao Lu pulled out a gun and fired twice into her own installation, Dialogue. The dramatic incident caused a three-day closure, with Xiao Lu being detained by the police (though ultimately released). Though the exhibition was reopened, it was forced to close again due to anonymous bomb threats made against the event. In total, the exhibition had been open for only eight days and two hours, instead of the intended fifteen-day run.

Rise of Political Pop and Cynical Realism

Mere months after the controversial exhibition, the Chinese military opened fire on student and civilian protesters at Tiananmen Square, murdering an untold number of innocents in an incident that remains strictly censored today. The incident also permanently ended the dreams of avant-garde artists for a liberal, progressive socialist state, and propelled them toward a more cynical, realistic outlook. Political Pop thus emerged: an art movement driven by reexamination, subversion and satirising state propaganda. Artists turned the state-sanctioned Social Realism on its head, remixing common images of leaders such as Mao, Lenin, Stalin and Marx with folk, religious, and consumerist visual culture. Notable artists included Wang Guangyi, Liu Dahong and Yu Youhan.

Parallel to the development of political pop was the rise of Cynical Realism, a movement of artists disinterested with grand narratives and political resistance. These artists approached life with an air of indifferent cynicism: their works often depicted humans with enlarged faces, distorted eyes and humourless, soulless grins. Having abandoned all ideologies and ideals, their works embraced the absurdity of life, their human figures outwardly smiling but inwardly devoid of purpose and individuality. Artists included painters like Fang Lijun, Zhang Xiaogang and Yue Minjun.

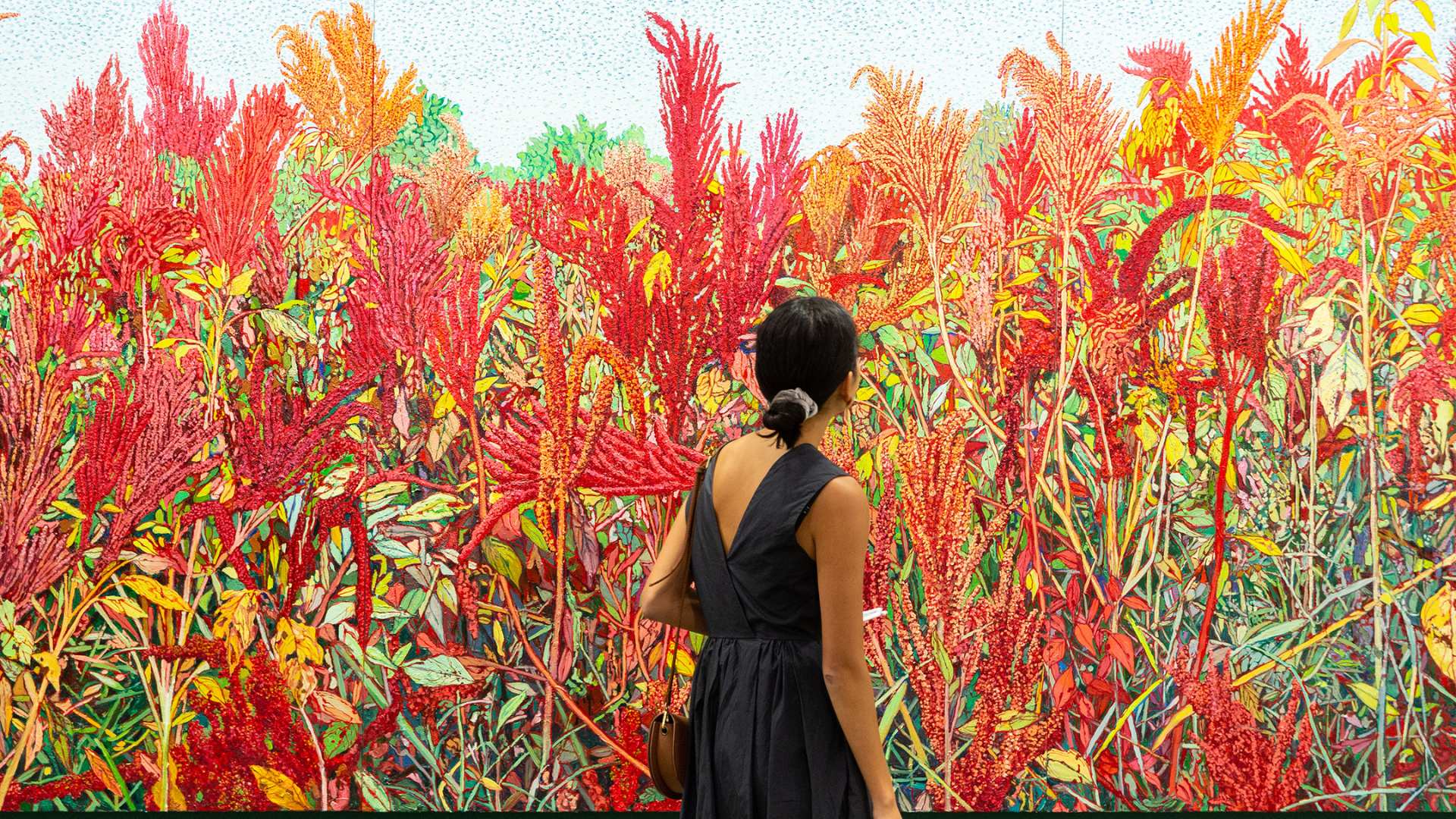

Post 2000s: Institutionalisation of Contemporary Art

Art museums sprouted throughout China, made possible by the influx of wealth to the government and businessmen. This was enabled by the economic expansion of China since the 1990s. National museums had long since formed a crucial aspect of propaganda efforts since the 50s, but due to a 90’s policy in which developers were rewarded tax breaks in exchange for building non-profit art spaces, private museums emerged and replaced these national museums as the most vibrant hubs for Chinese artists.

It began with a first wave in the late 90s, including the Upriver Gallery in Sichuan (the first private art gallery in China), the Teda Contemporary Art Museum in Tianjin, and the Dongyu Art Museum in Liaoning. The second wave occurred in the early 2000s, including the Today Art Museum and Taikang Space in Beijing, and the Shanghai Himalayas Museum in Shanghai in 2005. The surge continued into the 2010s, with 451 private museums established in 2011 alone.

The purposes of these institutions vary, with some intending to increase the visibility of Chinese contemporary art on the global stage, while others are more community-based, serving as spaces for education and art appreciation for the local populace. Notable museums include the Red Brick Art Museum, Power Station of Art, Yuz Museum, and the Long Museum.

In conclusion, Chinese art since 1976 has seen an incredible array of movements, from the rebellious Stars Art Group and the ’85 Avant-Garde Movement, to the rise of Political Pop and Cynical Realism, and finally to the institutionalisation of contemporary art. China’s art scene has both faced and overcome numerous challenges over the years, always evolving and adapting to the changing social and political landscape. Its future will undoubtedly continue to be as fascinating and complex as its past.