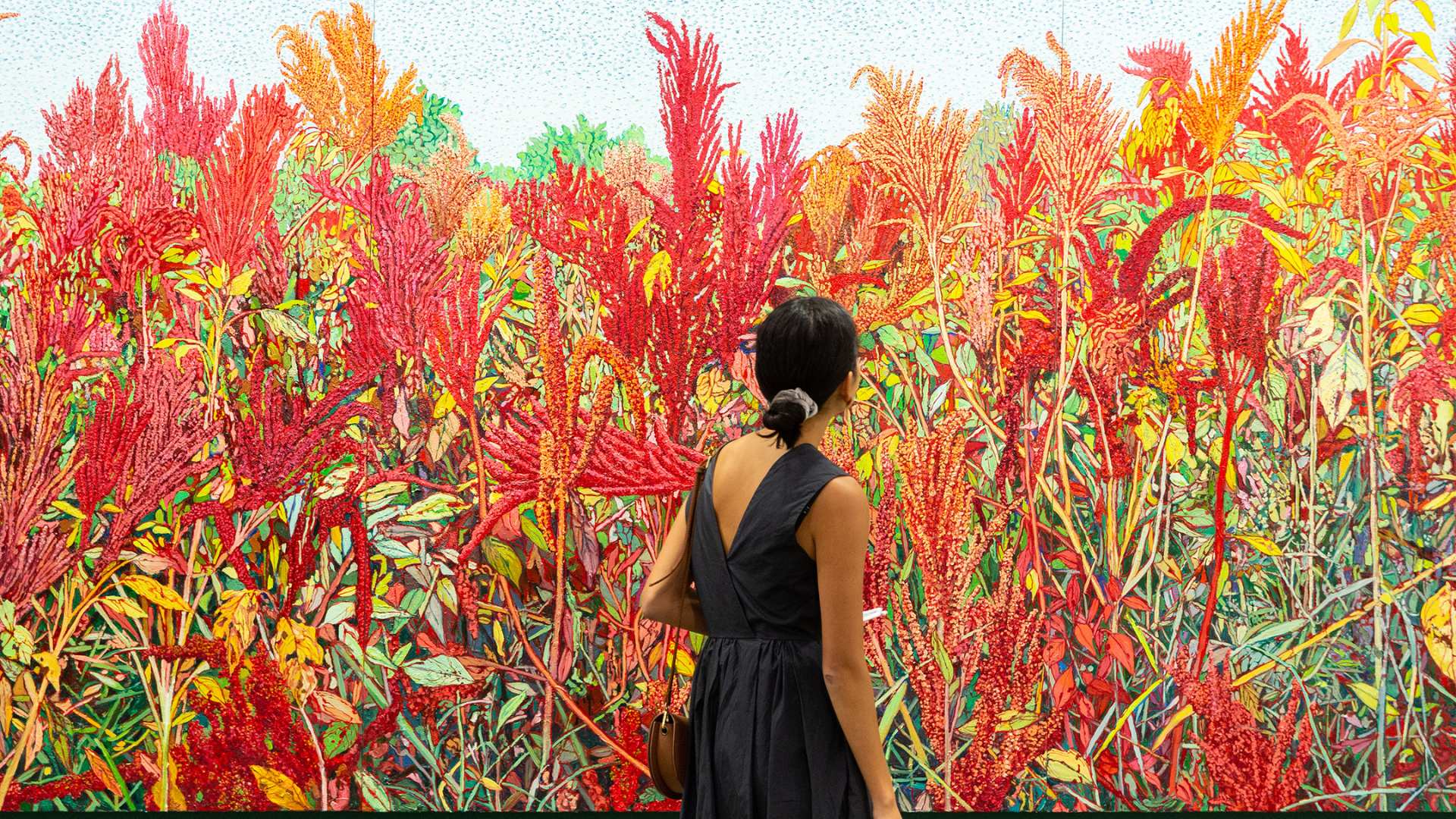

Printmaking is and has always been a crucial aspect of art. Due to its capacity for mass production, art prints allow ordinary people to access works of art outside of the museum space, and to own art without spending a fortune. However, beyond merely replicating other masterpieces, prints have had their own distinguished history and different techniques, being treated as original works which command high value. In this article, we will explore the basic mechanisms of printmaking, and some of the most prolific artists within its long and complex tradition.

Basics of printing

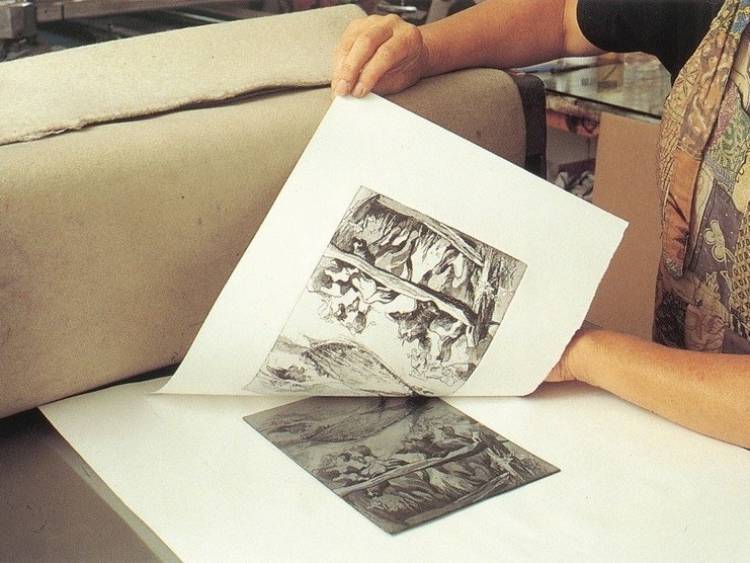

Printmaking involves the transfer of an image from a matrix to a flat surface. A matrix refers to any kind of template and can be composed of a variety of materials: wood, metal, stone, linoleum, silk, etc. The image is thus transferred from the matrix to the surface, and this process can be repeated multiple times depending on the durability of the matrix. Controlled pressure is usually applied to the matrix in order to transfer the image, and this requires a printing press or some kind of device, though pressure may also be applied by hand. (The Met)

Types of Printing

While sources differ, most agree that there are four main types: relief, intaglio, planographic, and stencil.

Relief involves cutting away the surface of the matrix to form lines and shapes. The raised areas retain ink and leave an impression on the surface, while the cut areas do not retain ink and constitute negative space. While woodcut is the oldest instance of relief printing, linocut is a more modern method that uses linoleum as a more manageable material for its matrix.

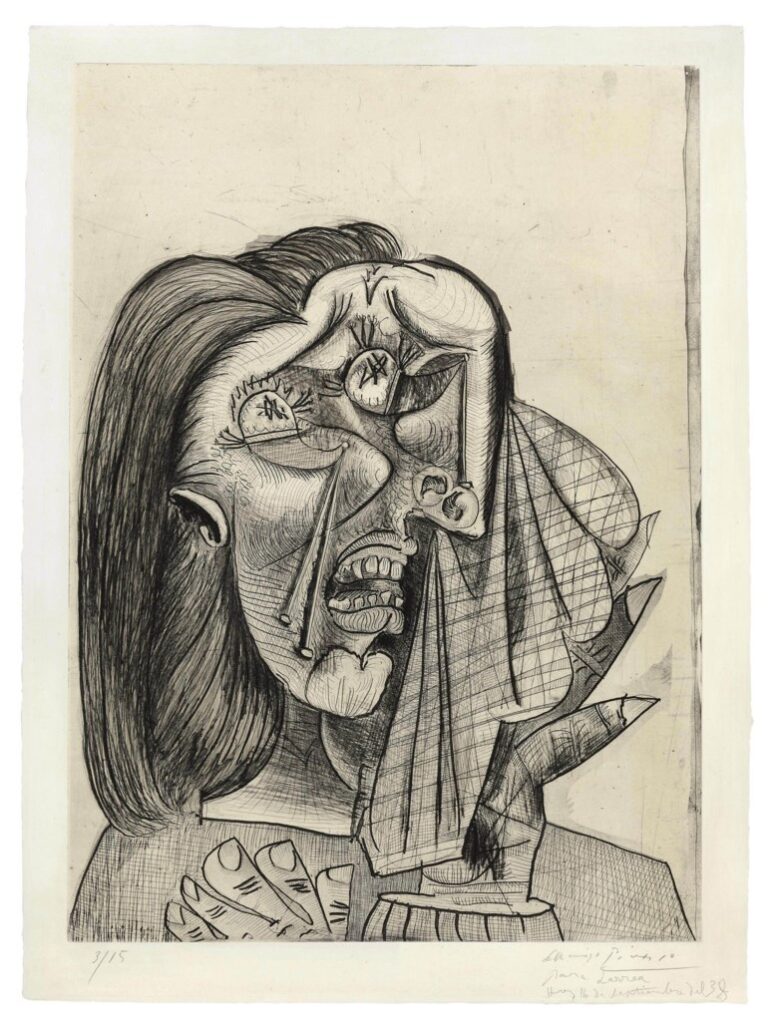

Intaglio is the inverse of relief: the cut areas form the positive space, and the uncut areas form the negative. The design is cut into the matrix, and ink is rubbed into the grooves rather than on the raised area, which is wiped clean. The ink is then conveyed onto the paper using considerable pressure: a roller press is often used, where the paper is squeezed between two bearing rollers and comes into contact with the ink-filled crevices. Examples include engraving, etching, and mezzotint.

Planographic printing involves utilizing a flat surface to impart images. Lithography is the most commonly known subset, in which a design is drawn onto a porous stone matrix with a litho crayon. The stone is then dampened with water before an oil-based ink is applied, which adheres to the crayon design while being repelled by the moisture in the stone. The paper is subsequently pressed onto the stone, allowing the ink to transfer onto the paper. This method allows for the design to be edited between prints, allowing for greater flexibility in the design.

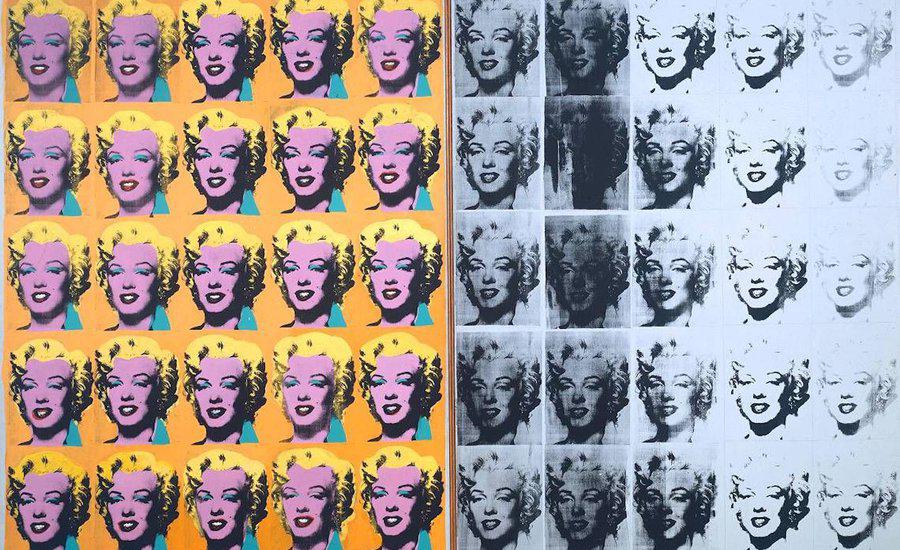

Stencil printing involves the artist passing ink or paint through the cut spaces of a stencil and onto a surface. This relatively simple technique has been around since the 9th century, and in the 20th century is used heavily in street art due to its fast and fuss-free process. It’s also used heavily in fine art painting due to its ability to create clean-cut lines and shapes easily; Roy Lichenstein used stencils to reproduce the half-tone pattern of popular comic books, and Picasso, Miro, and Matisse all used stencil prints in their works. Most notably, Warhol used screen printing extensively in his printmaking process, mimicking the techniques used in the mass production of T-shirts and other commercial merchandise.

A Brief History of Printmaking

The earliest printmaking is largely acknowledged to have emerged in 9th-century China and spread to the Islamic world. Up till 15th century Europe, printmaking was not perceived as an art form in and of itself, primarily used to create playing cards en masse and mass-produced religious iconography.

However, in the 1490s the form enjoyed a resurgence due to a rise in demand for printed books, which necessitated the use of the woodcut process as a cheap and efficient method for including illustrations. At the same time, the seminal works of Albrecht Dürer established printmaking as an artistic medium in its own right, being able to deliver the same nuance, expressiveness, and drama as a painting.

In the 19th century, new influences emerged in the field with the German invention of the lithograph, which allowed for greater fluidity and experimentation with the craft. Lithography became a favored tool for Impressionists like Monet, Degas, and Pissarro due to its ability to create soft lines and gentle gradients. Around the same time, Japanese woodcuts began to gain visibility, influencing Gauguin, Van Gogh, and others with their vibrant colors.

In the 20th century, Modern artists began to reexamine existing art forms and practices, prompting the rise of experimental and avant-garde art practices. In the same vein, printmaking took on a more experimental form, alongside other mediums such as paintings, sculpture, and so on. High-profile printmakers included Picasso, Braque, Matisse, and Rouault.

Currently, printmaking remains one of the most preferred methods for artists looking to rapidly and effectively express their ideas. Warhol famously used silkscreen printing in his works, aiming to comment on the proliferation of images in mass media culture. Hockney experimented with using the modern photocopy machine to make unique prints, manifesting his obsession with modern technology. Certainly, the fundamental mechanics of the printmaking process are concepts that artists and audiences find to be resonant with the consumerist, mechanized society we find ourselves in today.

It’s also interesting that some of the most valuable masterpieces in the world are not originals, but prints. At auction, Andy Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn, a silkscreen print, became the most expensive 20th-century artwork ever sold at $196 million. Likewise, Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa went under the hammer for $2.76 million, exceeding its highest estimate by almost 300%. It’s clear that the driving force of value in the market is not the originality of the work itself, but the signature of these influential, iconic artists.